Yerres Historical Society

|

Société d’Histoire d’Yerres

Yerres Historical Society |

|

|

Yerres duringthe 1939-1945 warThe occupation, the Liberation |

They contributed in the writing of this text:

|

The memory must be perpetuated

The Second World War left many countries and territories scarred. Yerres, like many towns and villages in France, was no exception, suffering four years of German occupation.

In our town, the memory of this conflict - during which thirty-two of its inhabitants "died for France" - refers in particular to the events surrounding the liberation of Yerres, which took place on August 27, 1944.

That day, American troops entered streets decked with flags of the victorious nations celebrating freedom finally regained! Four Yerrois engaged in the internal Resistance lost their lives as heroes during the events immediately preceding the liberation of their city.

In 2024, we are celebrating the 80th anniversary of this significant event in the history of Yerres, which the Commune, patriotic associations and residents commemorate with solemnity each year around the war memorial.

The Yerres Historical Society is offering us on this occasion a new publication on this painful page of our history, based on precious local archives, meticulously analyzed and put into perspective. May all those who contributed to this remarkable work be warmly thanked here.

At a time when the last survivors of this era are gradually leaving us, it is important that the memory of these terrible but nonetheless hopeful hours be perpetuated.

Happy reading to all!

|

Foreword

The text you are about to read was written by the members of the Société d'Histoire d'Yerres. We felt that the celebration of the eightieth anniversary of the Normandy landings was a good opportunity to remind the people of Yerres that their town was under German occupation for just under five years.

It is true that this anniversary does not have the prestige of a centenary like the one we commemorated ten years ago. But time passes and it is always better to mark the moment than to postpone the celebration of events until later. Tomorrow is another day! And then, will the time of lived testimony still exist in twenty years?

We've tried not to forget anything and to write truthfully! We have neither exalted nor hidden anything about this difficult period. We only wanted to tell the story, while carefully avoiding judging, as the great historian Marc Bloch asked us: “Don't judge”. Our society is a history society, not a court of law. Everyone is free to make whatever judgement they see fit.

On August 27, 1945, Yerres was liberated by a unit of the Third American Army, commanded by the very famous General Patton. Thus ended the nightmare of the German occupation after a little less than five years of the occupier's presence.

This small booklet aims to relate the main events that our city experienced during these dark years. Its size, necessarily condensed for publishing reasons, will not allow us to mention everything. The site of the Yerres History Society will bring you in the coming months the necessary additions to a history that we want to be more exhaustive.

To find out about the period, we have delved into the many archives, first and foremost those of our commune, but also those of Essonne, which are very comprehensive, Yvelines, the National Archives and those of the French Defense Historical Service. We have deliberately omitted the documentary references that would have made the already dense text more cumbersome, but they will be found in the final version.

People from Yerres, some still with us today, others who have passed away, have given their testimonies and given us documents. We would particularly like to thank: Mrs Denise Loubet-Prospéro, Mrs Pernette, Mrs Paternoster, the de Kerland family, Didier Leroy, Véronique Roncin-Gossiôme, Philippe Koehl. Thanks to Didier Leroy, we had access to the diary of Grégoire Nicolas Finez, a painter then in residence in Yerres.

A very big thank you to Mrs Marotta, in charge of the Yerres Archives, who has always responded to our multiple requests for consultations with competence, speed and… good mood!

Enjoy the reading!

|

Yerres at the beginning of the war

A survey by the Feldkommandantur of Versailles carried out in September 1940 gives us the main information on the city. Reflecting the German organization, the occupier asked the mayors for a very detailed and quantified description of their municipalities.

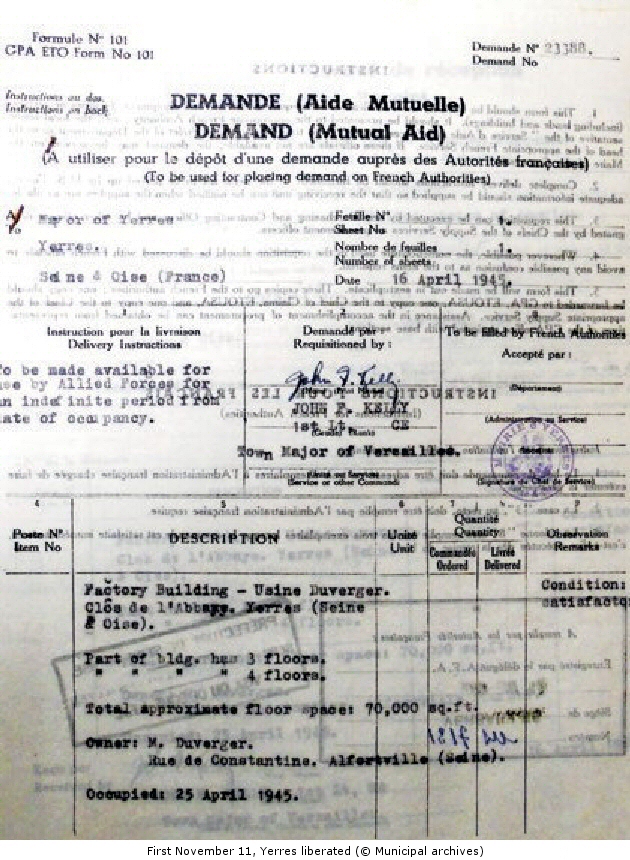

Yerres, in 1940, was a medium-sized town in the suburbs of Paris. It had grown quite rapidly, with 2,300 inhabitants in 1921, 3,800 in 1926, 5,200 in 1936, and housing developments had already appeared. It belonged to the department of Seine-et-Oise, sub-prefecture of Corbeil and canton of Villeneuve-Saint-Georges. It was neither really agricultural nor industrial, although it had a spinning mill (Laines et Tricots BZ.F) located in the former abbey, premises which seem to have been occupied until 1940 by the Duverger establishments.

The cultivated area (including gardens) is around 450 hectares, and vineyards now account for only half a hectare, but there are 6 hectares of market gardening, notably in rue de Concy, and only around twenty people working in agriculture, growing wheat and fodder. The forty or so hectares of wheat grown have a yield of 20 quintals per hectare.

It only has three large farms (Henry, Paternoster, Crouillebois) and produces only half of the milk and a few percent of the potatoes it needs. There are no slaughterhouses but two special "killing places".

There are many shops: 18 grocers, 7 butchers, 5 shoemakers, 5 bakers, etc., and 18 cafés.

On the other hand, the large bourgeois properties are still present and bring what we would call today service activities; there are, for example, 2 carpenters and 13 masons. Many craftsmen are present in Yerres, but many Yerrois work outside Yerres, in Villeneuve-Saint-Georges in the SNCF workshops, but also, already, many in Paris.

Connections with the capital are still mainly by train, via the Montgeron, Brunoy and Villeneuve-Saint-Georges stations.

A bus service (the Martelet buses, in particular) connects our town daily and several times a day to the neighboring towns and to Paris. The town has two cinemas, each with about a hundred seats.

Just before the war, the town had 281 individual cars, 7 buses, 12 trucks and 5 gas pumps. Two garages provide repairs. Yerres has 158 telephone subscribers (which is not automatic, the town hall number is 26 in Yerres), but no bank.

The town has a preventorium (Calmette centre) with 128 beds, two general practitioners and three dentists. The school population is large: twenty-one classes with as many teachers, with 370 girls and 270 boys. Yerres is also under the jurisdiction of the Brunoy State Police and the gendarmerie of the same town. Contributing to public hygiene, the town has shower baths.

In conclusion, a small, relatively fast-growing town, already overtaken by the urbanization of its outlying areas, but which still retains many of the fine residences of past centuries.

|

The events of 1939-1940

France and England declared war on Hitler's Germany on September 3, 1939, to come to the aid of Poland, which had been invaded by the German army on September 1. The mobilized Yerrois joined their assigned corps according to the call-up dates shown on their military booklet.

For nine months, the so-called “phoney war”, nothing happened on the French front, apart from a small operation in the Saar to relieve the Poles, which was quickly brought to an end.

On May 10, 1940, the Wehrmacht crossed the Meuse at Sedan and German armored units raced towards the Channel coast, splitting the French armies in two, a small part of which was evacuated by sea to Dunkirk. German forces then invaded France. Paris, declared an open city, was occupied on June 14, 1940. A government led by Marshal Pétain in Bordeaux requests an armistice which is signed in Compiègne on June 22, 1940. France is divided in two with an occupied zone in the North, in which Paris and therefore Yerres are located, and a so-called free zone (or "nono" because "not occupied") in the south with Vichy as the capital where the French government is installed. The French Republic (Liberty, Equality, Fraternity) becomes the French State (Labor, Family, Fatherland).

On May 10, 1940, the Wehrmacht crossed the Meuse at Sedan and German armored units raced towards the Channel coast, splitting the French armies in two, a small part of which was evacuated by sea to Dunkirk. German forces then invaded France. Paris, declared an open city, was occupied on June 14, 1940. A government led by Marshal Pétain in Bordeaux requests an armistice which is signed in Compiègne on June 22, 1940. France is divided in two with an occupied zone in the North, in which Paris and therefore Yerres are located, and a so-called free zone (or "nono" because "not occupied") in the south with Vichy as the capital where the French government is installed. The French Republic (Liberty, Equality, Fraternity) becomes the French State (Labor, Family, Fatherland).

On November 11, 1942, after the Allied landing in North Africa, the free zone was in turn occupied by the German army, but a French government remained in Vichy, this time directly under German control. Throughout the war, the French administration remained in place and continued to manage the country, but under German directives.

We do not know the exact date of the arrival of the first Germans in Yerres, probably after the occupation of Paris. The occupation apparently began in the last half of June.

On June 14, 1940, the day Paris was invaded, the brand new bridge over the Seine (it was less than a year old) at Villeneuve-Saint-Georges was blown up along with the old one, still in place, which was only used as a pedestrian bridge. It was no longer possible to cross over to the left bank of the Seine. Little by little, traffic difficulties due to the occupier's controls and the lack of fuel would restrict the movement of the populations that the exodus had thrown onto the roads. They would return, sometimes helped by the German army.

In Yerres, as in other towns on the outskirts of Paris, life seems to come to a standstill, or nearly so. Many of the men are prisoners in Germany, economic activity is suspended and general unemployment makes life very difficult for families. The people of Yerres will have to adapt to survive. |

Municipal life from 1940 to 1944

It was a complicated one, and even more so in our area than in many of the surrounding communes. A few months before the outbreak of war, the municipal council elected in 1935 was still in place. The mayor elected on May 17, 1935 with twenty-three councillors was Mr. Léon Teillac. Predominantly center-left, the council included twenty-three councillors, two of whom were members of the French Communist Party.

After the signing of the German-Soviet pact on 23 August 1939 in Moscow, the then President of the Council, the radical Édouard Daladier, dissolved the Communist Party on 26 September 1939. An article of the law also allowed for the suspension of communist councillors from the communes and for the replacement of the councils by "special delegations".

Following a blockage of municipal action by a minority of the council, and for other reasons which affected private life and which we cannot discuss here, on 27 January 1940, the Yerres council was "suspended until the end of hostilities". It is replaced by a special delegation, as in many other communes in the Parisian suburbs, for example Villeneuve-Saint-Georges, a town where the municipality is entirely composed of elected communists.

This delegation will have only three members appointed by the prefect (in fact the Minister of the Interior, Mr. Georges Mandel): Mr. Perrault, retired radical teacher, president, Mr. Mailliet, retired trader, radical, member, Mr. Cordier, retired teacher, socialist sympathizer, member. None of these members has exercised any elective mandate before this date. This delegation is of the political color of the government in place, that is to say radical, and it is it that will have to face the first difficulties of the year 1940. Here is his declaration to the people of Yerres upon taking office:

"The special delegation will not perform miracles. It will energetically defend the interests of the commune. In all circumstances it will strive to reconcile the general interest with the legitimate interest of each. Let us be calm, united, disciplined, to win the war that has been imposed on us. When peace has returned, true peace, victorious peace, France, land of freedom, hardworking France will know how to ensure prosperity and now, let's get to work!"

Almost a year later, on June 22, 1941, this time under the Vichy regime, a new council was installed (still unelected) by the regime. This time, it was made up of twenty members chosen by the prefect, but M. Perrault continued to chair what was still a delegation; for simplicity's sake, however, we'll call him mayor. Five councillors, including Messrs Gerbé and Genest, were members of the 1935 council.

It was this council that would manage the town of Yerres until 1944, a very difficult management due to the occupier, and to Vichy, which had a certain philosophy of public action in line with the ideology of the regime: the "Révolution nationale", shortages of all kinds, captivity or deportation of inhabitants (Jews, resistance fighters, prisoners), etc.

The Liberation, as we shall see, will open a new chapter in communal action and, for other reasons, it will be as complicated as the previous one. We will discuss this later.

|

Exodus and refugees

As the German army approached, the French, mainly city dwellers, left their homes. There were two reasons for this: firstly, fear of the fighting, which, as we know, did not spare civilians - as was the case in 1940 with the strafing of refugee columns by the German air force - and secondly, the rumors that resurfaced, as in all previous eras, about the atrocities committed by the Germans. The exodus!

Between six and eight million people, young, old, priests, nuns, firefighters, including national and municipal civil servants, public services in general, took to the road, heading south, blocking the routes and compromising the attempts of the French army to resist the invader. The scenario was the same as in previous eras. Since the invasions of 1814, then in 1870, in 1914, the French had been fleeing before the enemy. But in 1940, the population volumes were much greater. It was every man for himself! The Exodus with a capital E. It was the Belgians and the Luxembourgers who gave the signal and the flow of new arrivals grew.

We have two testimonies, first that of the painter Finez who lives on rue Raymond Poincaré, not far from the farm of Mr. Henry, of whom he is a friend, and that of Mrs. Prospéro. Here, first, is that of Mrs. Prospéro:

“Two columns were advancing on either side of the road. In the middle, a few rare crowded cars. Horse-drawn carts, a few bicycles… The miserable people, tired, some pushing a wheelbarrow, in which an old man had been placed, others pushing baby carriages. They were very unfortunate and miserable people, tired, exhausted. These people, we were told, were coming on foot from the east of France. Cars were advancing slowly, but mother told us “they won’t go very far, there’s no more petrol”. There were also a few trucks stuffed with all sorts of things, crates, mattresses, bales, etc. Some time later, the same thing happened again: there was the rout of the French army. The soldiers were dirty, tired, exhausted. They were marching without order, in disarray. They were dragging themselves along like the civilians we had seen passing by."

"Little by little, the people of Yerres became afraid because of the imminent arrival of the Germans - many - most of the people of Yerres left their small town - in the end, there was almost no one left. In the town centre, there must have been only about fifteen people left…"

Finez, with a lively pen, describes the scenes unfolding before his eyes:

"In front of our house there was the uninterrupted procession of fugitives who, since June 9, had not stopped pouring in. We had seen entire villages pass by, the entire Blanc-Mesnil farm with 50 head of cattle had passed by… everyone was fleeing to Melun… going down the Camaldules hill, the crowd of fugitives became worrying.

"… a number of carts, carts passed by carrying entire families, one of them harnessed to three horses and overloaded with people of all ages collapsed in front of our house… a horse fell on the descent. Many accidents on the descent of the Camaldules, the fugitives not expecting this rapid and dangerous descent… Uninterrupted procession of panickers, cowards, and fearful people."

And Finez sees what remains of the French army passing by:

"A dozen young soldiers with or without weapons but all on bicycles with a jaded but rather cheerful look are heading towards Brunoy where they say they have gathered at the Pyramid. Don't worry, they say, the war is over. The Germans are in Paris and Paris is an open city."

"In the evening, the rout, a whole regiment passes in front of our house, the real rout, men exhausted with fatigue no longer saying anything, sad and heartbreaking parade in the rout of a whole troop that continues to march all night…"

A spectacle that all French cities have experienced, especially north of the Loire. Two thirds of the Parisian population within the city walls leave the city.

A lot of people from Yerres have obviously left, and here too Finez sheds some light. He and his friend Henry are going to prevaricate a lot. The crowd in front of their home urged them to leave quickly, but Finez wanted an evacuation order and after much hesitation (he had prepared his cart just in case), the two families decided to stay (Henry had his cows and could hardly abandon them).

This will not be the case for all the people of Yerres. Finez writes for the day of June 14:

“No evacuation order was received, but the postmistress and her employees had left at midnight, which meant that all the commune's shopkeepers, the 3 bakers, the butchers and the pork butchers, with the exception of Mme Charles, had fled… I found M. Perrault, president of the special delegation, who told me to stay… And he added: As the masters fled, the servants followed…”.

Other Yerrois therefore left, but, apart from what Mrs Prospéro tells us, we have no precise assessment of the importance of these departures. Let us also remember that the Martelet coaches were used in the exodus of the Yerrois population on the way there and back; they even had a few mishaps!

To his credit, the mayor is still at his post, as many of his fellow mayors have not hesitated to abandon their constituents, including the town clerk, Mr. Thomas. What about the municipal staff? A number of them left their posts and fled the town without being ordered or authorized to do so. When they returned, sanctions were taken against them. Nine men and six women returned after a fortnight to three weeks' absence, meaning that some fifteen people - a large number, almost fifty percent - would be sanctioned. At the time, Yerres had no more than forty municipal employees, not all of them full-time.

The president of the delegation had, on his own authority, dismissed six municipal employees; the prefect reminded him on August 5, 1940, that he would have had to convene a disciplinary committee to rule on their case.

The president justified himself by replying to the prefect that the population of Yerres had shown great hostility towards the fugitives, some of whom “left taking the fire engine with them…they were also accused of stealing petrol”, and he added: “Moreover, even before the war, certain employees had already made themselves unbearable due to their arrogant attitude towards the public”. It seems that the atmosphere in Yerres was not always serene before the war!

The culprits will return, and the fire engine will be returned, intact, to its garage! The penalties are modest: loss of pay for the duration of their absence, i.e. from eight to fifteen days.

There were many foreigners in Yerres at the beginning of the war, but none of them seemed to be people displaced by the war. In the survey conducted by the Feldkommandantur in September 1940, there were 23 Italians, 23 Poles, 3 Russians, 2 Chinese, 2 Germans and one Finn. They lived in Yerres and were therefore not refugees who had recently arrived. The large number of Italians reflects the strong Italian immigration to France, mainly for economic reasons, between the two wars. Since the document only speaks of foreigners without specifying whether they were French (and foreigners by origin) or not, it is possible that these adopted Yerrois retained their nationality; this is a certainty for some.

It does not appear that refugees from the exodus stopped for long in Yerres and remained there during the war years. In September 1940, however, there were "24 refugees from the North" according to the census required by the Feldkommandantur. Their presence may have been only temporary. Another note from 11 May 1945, however, specifies that there were still eighteen civilian refugees in the commune at that date, although neither their arrival dates nor their origins are known.

|

The occupying Forces

We therefore do not know exactly when the first Germans arrived in Yerres, most likely in the second half of June 1940. In fact, some clues show us that the mayor met the occupier for the first time on June 17, 1940. Mrs. Prospéro describes the arrival of the Germans without giving us the date:

"Then the Germans arrived in Yerres. They paraded in the street, in front of the Hôtel de la Poste, on a beautiful day. They were young, arrogant, proud, disciplined, well-dressed. We watched them pass, led by the band, what could we do? We suffered them."

The painter Finez would only see Germans passing on the N19 road in front of Grosbois on June 18: “trucks packed with bare-headed German soldiers arriving in Paris at full speed, standing and singing hymns…”

Mr. de Kerland reports that the first German sidecar was welcomed at Yerres by a representative of the Communist Party who had uncorked a bottle of wine in the name of the German-Soviet pact. Whether this is a true or false anecdote, or even embellished, we do not know, but it is plausible in the atmosphere of the time!

Still, other Yerrois received the occupier rather coolly. Finez writes that the mayor posted a note on August 4, 1940 saying: "I most imperatively invite the entire population to maintain an attitude of absolute correctness towards the authorities and German soldiers." This note followed the complaint of a German officer whose soldiers "had been victims of rudeness.".

Therefore, the Germans arrived in Yerres around June 15-18, and a sort of Kommandantur, even if it did not yet bear the name, set up home with us at an address that we cannot specify exactly, perhaps at the Abbey or, rather, nearby, at Val Ombré. It would remain there, it seems, until November-December 1940.

All French people of the time talk about the Kommandantur, most often with fear. In fact, there were several depending on the French administrative level with which they were associated: Feldkommandantur for a department (Versailles then Saint Cloud for the Seine-et-Oise), Kreiskommandantur for a sub-prefecture (Corbeil) and Ortskommandantur at the level of a commune. The latter will be present in our country, as far as we can judge, until November-December 1940 and it will be under the direction of Captain Hoppe of the Wehrmacht.

After this date, the presence of a Kommandantur in Yerres is not proven, which does not mean that the occupier is no longer present among us, but he is no longer stationed there, except in special circumstances. Mrs. Pernette, who arrived in Yerres in 1941 and was then about ten years old, does not remember seeing any Germans.

From now on, Yerres will have to deal with the occupying authorities, although the French administration remains. Almost all correspondence between the city and the Germans passes through Corbeil, which effectively implies that there is no longer, or not at all, an Ortskommandantur in Yerres. The mayor will also have the opening hours of the Corbeil Kommandantur located at the Hôtel Bellevue posted.

The armed wing of the occupier is the Feldgendarmerie present in the Kommandantur. Military police of the German army, it plays a bit the role of the French gendarmerie and controls papers, traffic, the French police, etc. The Feldgendarme is recognized by his gorget, a sort of identification plate held by a chain around the neck.

Finally, anecdote, the Germans obviously demanded the surrender of all the weapons that the Yerrois could hold. The mayor will hand over to Corbeil, to the Kreiskommandantur, 39 hunting rifles, 19 carbines, 29 revolvers and… 4 military rifles, as well as some ammunition. Mrs. Prospéro declares that her father had a Lebel rifle that the family buried in the garden. Other Yerrois certainly acted in the same way.

Some Yerrois are regularly summoned to Corbeil, often because they are suspected of being Jewish and, if they do not attend the summons, they are threatened with "coming to get them". This can also be for questions related to work in Germany.

A summary by the mayor on the German occupation dated November 1943 lists the requisitioned buildings with their evacuation date (in parentheses). Here are some of them:

Abbey (January 15, 1941), Le Manoir rue Basse (December 19, 1940), Château de la Grange (September 15, 1941), 4 rue des Écoles (December 19, 1940), Hôtel des Camaldules (December 19, 1940), 29 rue des Camaldules (December 19, 1940), 2 rue de l’Abbaye (December 19, 1940), 7 rue de l’Église (December 19, 1940), Le Val Ombré (December 19, 1940). 3 rue de l’Église (September 20, 1940), etc., a total of 13 buildings.

In addition to the requisition of buildings, there seem to have been those affecting individuals. Thus, Doctor Accad, on Rue Jacques Bouty, housed between 31 July and 17 December 1940 between 31 July and 17 December 1940 between 9 and 11 non-commissioned officers and soldiers. Finez, living on Avenue Raymond Poincaré, housed a non-commissioned officer, whose rank we do not know, named Stegemann, and a first class Schmidt, from 31 August to 17 November 1940. On 30 August he had "welcomed" a captain. In total, it seems that there were 53 requisitions of premises in private homes. The residents were compensated in proportion to the length of their stay. All the documents therefore show us that the German army left Yerres at the end of 1940, but perhaps not everywhere, and until 1944, when we will note new arrivals!

A possible exception is the Château de la Grange. We read above that the Germans left the château on September 15, 1941. However, another document dated February 20, 1942 specifies that 5 officers, 60 men, 4 automobiles and 5 horses were stationed there without indicating the period of occupation! Better still, another German occupation of the Château de la Grange is reported in another text. A German detachment settled there in January-February 1941 under the command of Lieutenant Schmitt and remained there until May 7, 1941, the date on which the electricity concession company (Sud-Lumière) interrupted its deliveries because the site was no longer occupied, but, it wrote, remained requisitioned.

We do not know what destinations this detachment had. It required a large civilian workforce, mainly male, ranging from five to ten people, for its operation. The president of the delegation was referring to the salaries of the employees who were paid by the hour. They are all identified as laborers, which suggests that there was some sort of industrial activity on site at the time and that this unskilled workforce contributed to it, but we do not know which one. Didier Leroy reports that it was, according to Mr. de Kerland, an aircraft engine repair shop, which seems strange! Another testimony speaks of a hospital.

Last passage, from June to July 1944, and even for the last one on August 10, only a fortnight before the liberation, Yerres had to house several dozen Germans, most often officers (including two generals) who seem to have belonged to the Todt organization and whose previous stationing is unknown. These last passages obviously correspond to the withdrawal of German forces after June 6, 1944, but such a long presence raises questions unless the requisition was a matter of principle and the occupants succeeded one another.

Mr. de Kerland tells us that the Germans demanded the designation of five hostages as early as 1940 to guarantee the safety of their troops. Five volunteers designated themselves: the priest Hoff, the mayor Mr. Perrault, Mr. Bardillon, Mr. Eddy de Kerland and Mr. Sirot. The municipal documents do not mention this episode, which nevertheless remains very probable and common at the time.

It is quite difficult to imagine what life in the communes and therefore in Yerres must have been like. We must rather imagine a willing or unwilling acceptance of the occupier at least until the last months of 1942: things would change with the events in North Africa, the invasion of the free zone and the institution of the Compulsory Work Service. For several months, cohabitation between Germans and Yerrois would not be too conflictual, as everywhere in France.

The German soldiers, isolated or in small groups, move around the city, go to the cafés, from which they do not always emerge lucid and walking straight, enter the shops (which no longer have much to sell!), rub shoulders with the inhabitants. They are no longer armed troops parading through the streets in goose step. Yerres is not a German military camp and the soldiers there are few in number; life goes on, materially much more difficult than before, but without marked clashes.

Yerres should not be considered as a commune living under tension where social life between the occupying and occupied communities does not exist. Contacts take place, rapprochements are made and this is why at the Liberation, so many individual behaviors will be criticized, or denounced, or worse, condemned, by those who will think that they had reasons to do so.

Nor should we always see ideological rapprochements. As everywhere in France, the Marshal's government was widely accepted in 1940, but there were probably very few real collaborators in Yerres and even fewer sympathisers of Nazi Germany. On the other hand, there were certainly opportunists who tried to take advantage of a relationship with the occupier. Some places were more frequented than others, habits were formed, which would fuel rumours of all kinds after the war.

|

Some glimpses of daily life

The conditions of daily life can be understood in all sectors and in many aspects, both in the area of municipal decisions and in the private or family context. Local deliberations are most often dictated by national instructions, or even by those of the occupier relayed by the prefect and the sub-prefect. The testimony of Mrs. Denise Loubet-Prospéro is valuable to us, to help us discover this period rich in problems and threats.

During the war, we will often resort to “resourcefulness” to “survive” and try to overcome the difficulties that lie ahead. The people of Yerres endured shortages, here as elsewhere. The almost five years of war saw harsh climatic conditions and made life more difficult. Mrs. Prospéro tells us:

"During the war years, it was extremely cold. In winter, frost came quickly, the winters were terrible, it was cold, no heating. When we went out, grandmother would put a folded newspaper under our sweater or jacket. We also put some in our clogs. The newspaper was supposed to protect us from the cold."

Here are some decisions of the special delegation:

The municipal council of September 7, 1939 (which was not yet a special delegation) decided, "in view of the slowness of the senior administration and the serious events that had occurred, to have an alert siren installed at its expense and asked the administration for a subsidy, as well as the purchase of 50 gas masks intended for the needs of the passive defense services."

The first decisions attempted to provide answers to multiple difficulties. Throughout the war years, the municipal council was mainly concerned with security, supplies, social and medical aid: this was the daily routine of its meetings, the frequency of which increased in the first months of 1940 (one per month), but it should be noted that there were no meetings between May and September 1940. Here are the most significant contents from 1939 to 1945.

From October 15, 1939, passive defense was organized by the "project of developing trenches near school buildings to ensure the protection of children {work} which will be carried out by the unemployed for 5 francs per day". At the same time, others were dug in the Grande Prairie to prevent planes from landing.

On March 21, 1940, the census and the establishment of food cards were carried out.

On September 3, 1940, the Commune had to provide for the “treatment of temporary town hall staff because the employees had left before the German advance.”

And on August 10, 1941, it was decided to purchase a proof of the burin portrait of Marshal Pétain, which would have consequences four years later.

From December 1941 onwards, all deliberations made mention of aid to be given to the wives and children of prisoners of war. Many businesses were abandoned.

Projects are postponed (physical education platform, showers, bus shelters), while public holidays are cancelled. Patriotic holidays (November 11) are now prohibited. However, a party was organized on March 19, 1944, to provision the Prisoner's Fund, which we will discuss again. A report from April 1 indicates that it would ensure that each prisoner who had not yet been released would receive an amount that should reach a minimum of 1,000 francs upon his return.

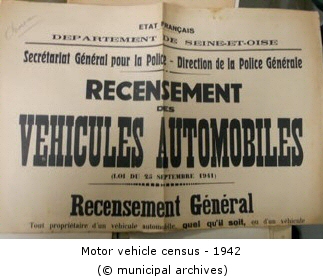

Finally, let us recall that the mandatory curfew at 10 p.m. made Yerres, like all other cities, a dead city. Everything, during these years, was rationed, restricted and counted, including bicycles, which would be registered. During the war, there was no more petrol. The cars were then equipped with so-called "gasifier engines" by gasification of wood, a rustic form of the current LPG.

Finally, let us recall that the mandatory curfew at 10 p.m. made Yerres, like all other cities, a dead city. Everything, during these years, was rationed, restricted and counted, including bicycles, which would be registered. During the war, there was no more petrol. The cars were then equipped with so-called "gasifier engines" by gasification of wood, a rustic form of the current LPG.

Denise Prospéro's notebook of memories contains a great number of details on the atmosphere in Yerres. The pages relating to this sad period, written with the emotion of the young child who lived through these events, express well the intensity of the anxiety felt. The harshness of the living conditions, due to shortages, often requires "self managing". Here are some of her thoughts in bulk:

Denise Prospéro's notebook of memories contains a great number of details on the atmosphere in Yerres. The pages relating to this sad period, written with the emotion of the young child who lived through these events, express well the intensity of the anxiety felt. The harshness of the living conditions, due to shortages, often requires "self managing". Here are some of her thoughts in bulk:

“They gave us vitamin-packed cakes made by a biscuit factory located near Pompadour, the Gondolo biscuit factory.

“We suffered terribly from the lack of food. At the shops, everything was missing. The shops were empty… As soon as we learned that a product had arrived, a queue would form in front of the shop, so we would spend hours waiting, standing, for very little food. The shops were empty. Mom would cook us Jerusalem artichokes. I quite liked them, in a salad with chervil, I liked it.

“But the worst and most detestable were the rutabagas, absolutely abominable. Mom cooked them in a kind of sauce, you really had to be hungry! We ate lard slices: I was disgusted! But it was the war, we were hungry, and finally, I liked these kinds of slices…

“At a shop in the rue de Paris, we bought our tobacco, including mine since I was entitled to it at 13, when I became a J3. Dad exchanged it for butter. We lacked everything, especially clothes and shoes; we made them from old coats. For ordinary people like us, the war was very hard. We had almost nothing to eat, except what we could produce ourselves, no or very little heating. How cold we were during those sad years.

“The electricity was often cut off. Dad had installed an old car battery connected to a tiny lamp. You could hardly see anything. Having knitted a lot myself, I kept some women’s magazines. This little magazine gave patterns for women, children and men.

“During the war, she showed women how to make balaclavas, gloves, scarves and warm socks for the men at the front. The war was hard for us, but for some, it was different: those who were black marketeers. They didn’t lose weight. The war was long, sad, cold, and so little to eat! A few vegetables from the garden, the animals from the chicken coop.

“One year, in the Bellevue garden, the potato harvest was looking magnificent; when mother and grandmother wanted to go and dig them up, thieves had gotten there before them.”

Much other information is contained in her notebook of memories which she donated to the Municipal Archives.

|

Life at school during the war

The smooth running of school life is a daily task.

It depends on the decisions of the Special Delegation and the deliberations of the School Fund. They deal with many subjects, including aid to canteens and the role of Secours National, a mutual aid organization brought up to date by the French State. The register of the School Fund is well kept, since public schools (and also private ones) continue to operate during this period.

Concerns for the protection of children at school appear to be particularly important. Thus in 1942, the National Relief was responsible for distributing casein biscuits to all school children..

For example, at the Centre school, rue Cambrelang, for the week of 16 to 21 November 1942, the distribution details indicate that 6 to 10 year olds received 2 rations, 10 to 14 year olds 4 rations, and 16 to 18 year olds 6 rations. These rations being daily, the total represents a package of 27kg400 for the week. The meal in the canteen, at a price of 2.50 francs, is very light; it included a soup broth, a few slices of Jerusalem artichokes, a piece of chocolate…

The management of the canteens is ensured by the School Fund Committee, whose meetings primarily concern the problem of food shortages. The deficit is getting worse. The causes are twofold: the number of students has increased; the price of meals is no longer in harmony with the cost of food. During hostilities, holidays, the general assembly will not take place. A supply of food (potatoes, pasta, dried vegetables, etc.) will be made available to the canteen staff to enable them to prepare for any eventuality.

It is planned to purchase wool for the production of knitwear made by school pupils.

On January 3, 1941, the president reported that he had been able to obtain a certain quantity of vegetables (rutabagas, turnips, carrots). Many children were currently undernourished. It was decided that a soup made from boiled vegetables would be served every day at noon to students who requested it. The committee would look for other solutions to somewhat improve a rather critical situation. On February 9, 1941, butchers were asked to “provide bones or some fat in order to serve the children a more substantial soup.”.

In the daily lives of schoolchildren, the fight against the Colorado beetle in 1941 took on the appearance of a "real crusade". This very useful activity gave rise to rewards. It was about saving the potato harvest, which was, as we will see, the basis of the diet along with the rutabaga and the Jerusalem artichoke.

A particular concern is the increasing absenteeism at school, absenteeism for which the causes are unknown. On December 15, 1941, the prefect sent a letter to all stakeholders (mayors, teachers, police, gendarmerie):

Child absenteeism reaches "12% of the normal number, while 2% of children never go to school and are not even registered." The prefect is not unaware of the consequences of the "circumstances", through "the shortage of clothes and shoes." The children find themselves left to their own devices. He refers to the law of August 11, 1936, which notably expresses:

"Whenever a school-age child is encountered in the street during school hours, you must have him or her returned to his or her family, inquire about the reason for the absence and inform the teacher. If the parents are not at home, which will happen frequently, the child must be returned to the school where he or she is registered. In the rather rare case of non-registration in a school, you must inform the Justice of the Peace of the Canton, who will summon the parents…"

The prefect ends his instruction by recalling all the delicacy with which it is necessary to act, "with firmness and measure", concerning childhood.

On November 10, 1943, the mayor sent a letter to teachers, mentioning "the speech of the Marshal of France, on the occasion of the opening of the National Relief Winter Campaign: two days of collections (November 13 and 14) in which children must be largely involved."

Students who successfully pass the Certificate of Studies and the entrance exam to a higher education institution are rewarded with a savings bank booklet worth 100 francs, but this reward is not retroactive. Free supervised study is granted to children from needy families. Secondary education becomes fee-paying.

But life will resume its course: on December 6, 1945, different commissions are installed. The Christmas party is organized. The re-eligible members are drawn by lot (by third every year).

The teaching staff seems to have continued its educational action with continuity and determination.

|

Prisoners of war and Compulsory Work Service (STO)

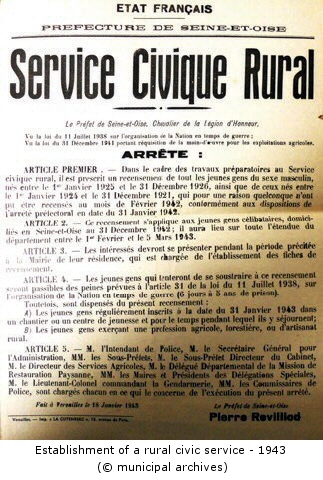

The French, and therefore the people of Yerres, will be called to go and work for Germany, first and foremost in France and then in Germany. In France, the occupier has begun major works for its own needs, but also soon for what is called the Todt organization, named after its leader. "Herr Doktor Todt" will be a major infrastructure builder of the Third Reich. It is he who will build the German highways, the Siegfried Line, the Atlantic Wall, etc.

The reason for this is simple: the Reich, having mobilized a large part of the male population, must replace the men it lacks in industrial and agricultural activities. It will therefore call upon the labor of the countries it occupies: Belgium, France, Poland, the Balkans, etc. Its demands will become more and more pressing as the war lasts and it will be necessary to replace the losses.

The first Yerrois will leave for Germany as free workers at the end of 1940, beginning of 1941. It should also be noted that prisoners of war would be able to transform themselves into free workers upon their request, in which case they will lose their prisoner status. German companies have hiring offices in France. Others will work in France to honor contracts made with the Germans

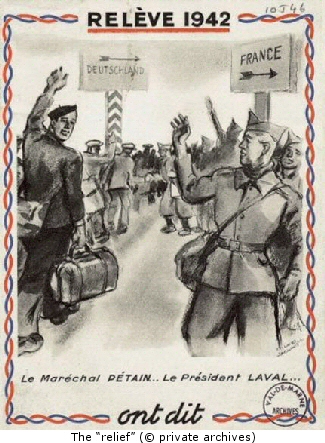

In June 1942, Pierre Laval, in agreement with the Germans, will advocate the "Relève". This involves freeing a French prisoner in exchange for three volunteer workers to go and work in Germany. This will not be a success, especially since Laval will think it right, during his radio message, to add: "I wish Germany victory!" As the Reich's need for manpower grew, the occupier will force Vichy to make work in Germany compulsory.

In June 1942, Pierre Laval, in agreement with the Germans, will advocate the "Relève". This involves freeing a French prisoner in exchange for three volunteer workers to go and work in Germany. This will not be a success, especially since Laval will think it right, during his radio message, to add: "I wish Germany victory!" As the Reich's need for manpower grew, the occupier will force Vichy to make work in Germany compulsory.

Before this decision, there was some pressure on the workforce to go and work in Germany under the banner of what would be called "forced volunteering". Not always forced work! Industry was "down" in France and unemployment was widespread, prisoners' wives had to live on a modest allowance, but on the other hand the wages paid by the Germans were attractive.

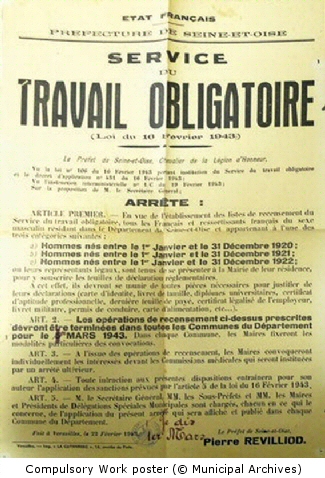

Then, in February 1943, the Compulsory Work Service (STO) was established, following the census of all men born between January 1, 1912 and December 31, 1921. A little later, in May 1943, young people born between 1921 and 1923 were again counted and provided with a work card that had to be presented with their identity card to prove their identity. This was the time when many young people joined the maquis to escape this STO. Here is a documented case of how a requisition to work for the occupier took place.

The mayor of Yerres received a letter from the prefect dated April 23, 1943, ordering him on the “formal order” of the Feldkommandant to requisition 11 men for the Todt organization and the prefect added: “this figure is imperative.”

The prefect ended his letter by writing:

“…I cannot let you ignore that the occupation authorities would be forced to take action against mayors who do not execute the general requisition order…”

And the mayor gives a list of eleven names (including an Italian) of Yerrois whose ages range from twenty-one to forty, eight are single and two are married with a child. This requisition follows others; thus, on January 14, 1943, six Yerrois are asked to appear before the town hall of Juvisy-sur-Orge on the 16th at 8:30 a.m. equipped with a blanket, warm clothes, a mess tin, table cutlery and food for 48 hours.

The mayor will try, without much success, to save a few conscripts by arguing that they are necessary for the life of the commune, for example passive defense or he will plead their retention for humanitarian reasons.

How many Yerrois left to work either in Germany or for the Germans in France? Based on municipal statistics, which are perhaps not entirely reliable, we find a total of fifty-two people (including some women) who went to work in Germany or Austria under the STO and about fifteen who are said to have volunteered; all returned in May 1945 after the German capitulation. The volunteers were not welcomed with open arms upon their return.

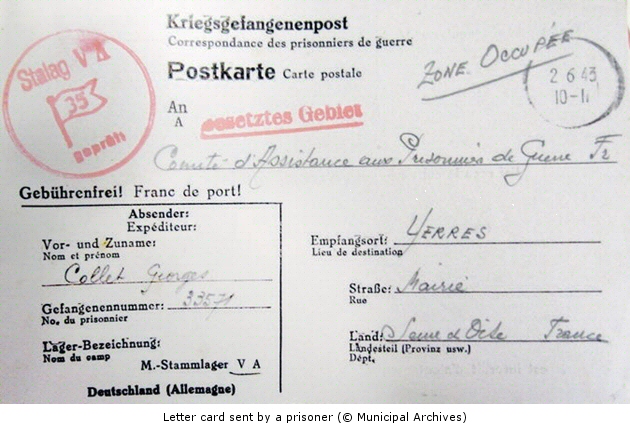

Let's see what happened to the prisoners. Almost all of them were employed by the Germans in the Arbeitskommando (work commandos) both in the countryside and in the city, but they kept their status as prisoners of war.

Germany took 1,800,000 men prisoner in a few weeks in 1940 and the armistice agreement provided that they would remain captive until the peace treaty which would never come…. For various reasons, only half of them would remain in 1945.

It seems that around 200 Yerrois would be captive in Germany. However, there would be releases, for example, for health reasons, but also as part of the "relief" and after certain agreements made by Vichy with the occupier; at the end of 1943 there would only be around 140 left, which seems plausible.

Prisoners and their families keep in touch through a postal service, but the number of correspondences is limited to one letter and two postcards written in pencil and subject to censorship. Families can also send parcels at a rate of one 5kg every two months and one 1kg per month using address labels.

Vichy, through the Prisoner of War Assistance Committee, also sent some, as did the Red Cross.

Vichy had established the Prisoner's Savings Account, a sort of savings account that was supposed to provide each prisoner with at least 1,000 francs on their return, a account that individuals and even municipalities could contribute to. Collections were held periodically.

The mayor was also a bit of a family advisor and helpful man, such as this letter from a prisoner in Königsberg asking him to look after his children, his wife "no longer being worthy of looking after them." The number of divorces increased significantly in France at the Liberation after the return of the prisoners, for reasons that are easy to imagine.

|

The deportation

It is estimated that around 85,000 people were deported from France between 1940 and 1945. Two categories are more important than others, those of Jewish origin and those of political deportees. The first convoy of French Jews left for Auschwitz on March 27, 1942. But there were deportees for acts of resistance and others simply because they were political opponents.

There were Jews in Yerres before the war; traces of them can be found randomly in the archives. For example, a Yerrois reported for other administrative reasons at least four houses on rue Pasteur and rue Boileau belonging to Jews in a letter addressed to the mayor.

They were French and perfectly integrated into the national community even if they were of foreign origin and had not acquired French nationality for various reasons. Fleeing the Third Reich, many Jews, originally from Germany or the Balkans, took refuge in France.

Vichy would promulgate two laws even before any request from the occupier: one on July 27 and the other on August 27, 1940, but it was especially the one of October 3, 1940 concerning the status of Jews, which aimed to exclude Jews from a certain number of public and private professions, that would really mark the beginning of the persecution.

On September 27, 1940, the Germans had published a law for the census of all Jews in the occupied zone as well as businesses belonging to Jews. The Jews of Yerres were invited to go to the town hall to be counted; unfortunately, the town archives did not keep the results of this census. We only have copies of some forms filled out by residents of Yerres.

We do not know if the Yerrois of Jewish origin wore a yellow star, which was mandatory due to the lack of severe sanctions. The archives do not give us any information on this subject.

We do not know if the Yerrois of Jewish origin wore a yellow star, which was mandatory due to the lack of severe sanctions. The archives do not give us any information on this subject.

From 1942, the roundups began, first hitting Jews of foreign origin, the most famous being that of the Vel d'Hiv on July 16 and 17, 1942, a roundup from which Bernard Nussbaum, Yerrois by adoption and then a Parisian, was one of the few to escape.

At the end of October 1942, a roundup of Jews of foreign and French origin was carried out simultaneously in several municipalities in our area: Yerres, Brunoy, Montgeron and Vigneux-sur-Seine. The people arrested were first grouped together either in a room of the town hall, as was the case for Yerres, or in the police stations of Brunoy and Montgeron. In the evening, they were all taken to Valenton where they spent the night in a property called Le Plaisir. The next morning they were taken to the Villeneuve-Saint-Georges station from where they were transferred by train to the Gare de Lyon, then were crammed into platform buses to the Drancy camp where they were registered on October 29, 1942. Here are the surnames of some of the Yerrois who were deported under the anti-Semitic laws:

Ella Davidovici, of Romanian origin, was the first of her family’s six children to come to France. She settled in Yerres during the 1920s. She lived at 3, rue de l’Église where she worked as a dental surgeon. On October 27, 1942, Ella was arrested by the French and German police at her home in Yerres.

Ella Davidovici, of Romanian origin, was the first of her family’s six children to come to France. She settled in Yerres during the 1920s. She lived at 3, rue de l’Église where she worked as a dental surgeon. On October 27, 1942, Ella was arrested by the French and German police at her home in Yerres.

She was first sent to the Valenton regroupment center before being sent to the Drancy camp on October 29.

On November 9, 1942, Ella left the Drancy camp on convoy 44 bound for the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp (Poland) where she was murdered, probably upon her arrival, on November 14, 1942.

Her sister, her brother-in-law and their children were later deported in 1942-1943 and did not return. Then came Fani and Arlette Sigal, Romanians of origin arrested in Yerres, interned in the Drancy camp on July 27, 1944, and sent to Auschwitz in July 1944. Arlette survived. Also in 1944, Jacques Van Duren was interned in May in Lithuania where he died. Stanislas Samuel Gotthelf, of Polish origin, deported on May 15, 1944, did not return; his son Guy was killed during the fighting of the Liberation. Mordka and Hana Szpirko, of Polish origin, were deported in 1943 and never returned, etc.

In total, around fifteen people, men and women, most of them of foreign origin, living or born in Yerres, were deported. Most of them did not return.

The deportees for acts of resistance or politics are fewer in number, five in total, of which only one, Mr. Boudeville, will return from Mauthausen.

The municipal archives lack precision. Indeed, the mayor sent to the prefecture in May 1945 a summary of the number of deportees and he reported eight under the name of "internees and deportees" without further details. It is therefore difficult to distinguish the categories. It is true that in certain cases the name of Yerrois is difficult to define depending on whether one takes into account the place of birth or that of residence.

|

The victims

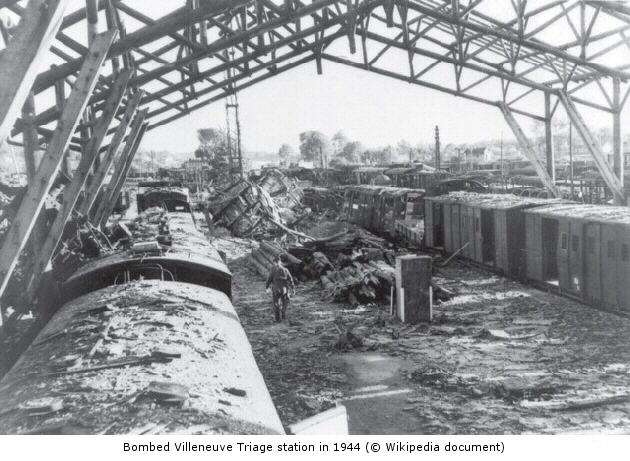

Yerres will experience a significant influx of another type of refugee, certainly from nearby, but they will also have to be welcomed. Our city is close to Villeneuve-Saint-Georges, and this city has a marshalling yard in its vicinity, Villeneuve-Triage, one of the largest in Europe at the time, and from there the trains that run in the South and West of France are formed.

This marshalling yard is a military objective. The destruction of the tracks prevents the movement of trains and paralyzes German military transport. The Allies, from 1942, will systematically, and increasingly as the date of the Normandy landings approaches, bomb the marshalling yards, the Americans by day and the RAF by night. The methods of bombing areas remain very imprecise. The planes fly in formation ("boxes" of planes) and drop their bombs on targets identified by colored target markers.

Now, the marshalling yard is surrounded by the urban fabric and many peripheral buildings are affected. For example, on April 9, 10 and 26, 1944 (on April 9, 437 buildings were damaged), the station was bombed, but also, damage that we now call collateral, buildings in Valenton, Créteil, Limeil, Brévannes, Corbeil itself which also has a marshalling yard. The bombings of the three days above caused the death of more than 300 victims in total, not counting the wounded.

There are many alerts and the population does not always have time to run to shelters, which are always insufficient in number. The property damage is very significant and many buildings are uninhabitable. With the destruction of the building, all the family heritage also disappears: furniture, clothes, personal papers, etc.

"The nights of August 20, 21, 22, 23 were terrible," Finez wrote. This was a sign of uninterrupted bombing all around Yerres. The homeless inhabitants became refugees who had to be sheltered and the neighboring communes, which had not been affected or had been affected only slightly, were called upon to help and had to take them in.

These systematic bombings were not the only ones and, from May 1944, the Allied air force experienced intense activity over France and in particular over the Paris region and did not deprive itself of opportunity bombings when the planes discovered targets, for example retreating German convoys.

It was a question of opening the road for the armies towards Paris and, more generally, towards the East of France. Eisenhower would have gladly avoided Paris, which had no tactical importance. It would take all the insistence of a de Gaulle for him to authorize General Leclerc to come and lend a hand to the Parisian insurrection triggered mainly, and somewhat thoughtlessly, by the communist resistance from August 19, 1944.

Mr. Perrault and his delegation are on the front line; they are made responsible by the prefecture forr welcoming the homeless and housing them in their municipality by requisitioning all or part of the apartments or individual houses. The procedure is simplified. The mayor informs the owner that he will go to the premises on a given day at a given time and if the latter is not there, the locksmith will open the door. Here, for example, is what an owner of a house located in Yerres, but living in Paris, received:

“Please bring the key to house 22 rue du Beau Site to the town hall tomorrow morning for requisition. Failing that, the house will be opened by authority.” Each owner had to obey a requisition order that he could contest, but not refuse. These are entire families that have to be rehoused. The lists that have reached us show families of two to five people; they give the address of Villeneuve-Saint-Georges and the address of Yerres. All the districts of the commune are concerned. Some Yerrois have even sheltered residents of Villeneuve-Saint-Georges in their garages where they worked during the day, then returned to spend the night in Yerres!

And the mayor has signed numerous ukases for housing requisitions. There are some holdouts, such as this lady who wrote to the mayor that although her house was not occupied, she intended to come and spend her summer holidays in Yerres. There were also amicable arrangements and some Yerrois willingly welcomed those who had lost everything. For example, one person living on rue de Concy accommodates fourteen people on her own. And then a certain number of leases were also signed amicably with payment of rent, which avoided requisition.

For others, it was more difficult. Another lady wrote, “…I have no desire to find my accommodation occupied and go to sleep in a hotel with a young child.” An awkward customer from Montreuil directly attacked the mayor for having designated his house “when,” he wrote, “there are many free houses,” and to name them without forgetting “those of the Jews, including two on Rue Boileau…”. The mayor himself asked the Kreiskommandantur to make “the building of the Jew Kraika available to him” to house two large families.

In total, if we are to believe the Municipal Archives, Yerres seems to have welcomed a little over 2,000 people, which is considerable if we remember that the population was just over 5,000 inhabitants. This also implies that our town had a number of empty or even under-occupied dwellings (houses and apartments). There were, of course, many disputes concerning the condition of the dwelling after the evacuation by the temporary tenant, but the mayor does not seem to have intervened and the archives are silent on this subject. The urgency often did not allow for proper inventories to be drawn up.

It certainly took a long time for the problems to be resolved!

|

Bombs over Yerres?

There are no military objectives at Yerres, however, as we have seen previously, there are many all around us and the distances separating us from them are so small that we cannot escape the hazards of the aerial bombardments that the Allies, with the technology of the time, apply to the area.

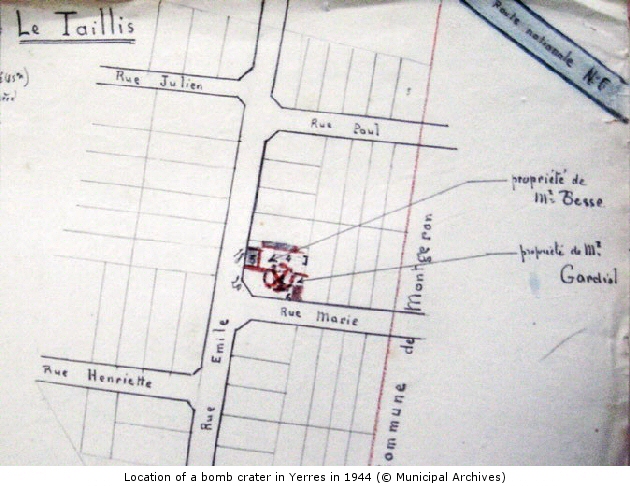

The people of Yerres were in the front row, as Finez describes: "it was a beautiful spectacle seen from our terrace, a real fireworks display, rockets of all colours rising in streamers into the sky, a general blaze of the countryside and the explosion of bombs." On the night of 14 to 15 July 1944, our painter wrote: "…for the first time since 1940, fear took hold of us…" The entire Yerres valley was lit up by red rockets and he saw a rocket that "passed over his house and headed towards Villecresnes" and he heard a "Boom" on the roof of his studio. The next day, he found on this roof a large flattened black tube of respectable size (1.60 m long, 18 cm in diameter and weighing 8.5 kg) which had caused minor damage. This was not the only incident.

The archives also mention a bomb that fell in the garden of a Yerrois resident, also during the bombing of July 14-15, 1944. The projectile made a funnel 8 m in diameter and 3 m deep in the garden of Mr. Besse at 18 rue Émile. The blast of the explosion caused other damage, cracking the walls of the house, uprooting fruit trees, destroying the common wall, etc. The crater was quickly filled by a clearing team from the municipality. Another Yerrois resident, Mr. Paul, a close neighbor of Mr. Besse, also suffered damage during the same bombing

Many other things were also falling from the planes flying over the region. The same day, at 25 rue des Côteaux, “a piece of an airplane”. Parachutes and rocket casings were also collected on rue de Concy. Under these parachutes were attached flare bombs of various colors, and slow combustion, which marked the bombing zones. Mrs. Pernette remembers seeing a parachute hanging in the branches of the cedar in Caillebotte Park and wondering where the parachutist was.

And then there were the fragments of the anti-aircraft shells that fell to the ground. The German anti-aircraft guns, installed at the Villeneuve-Saint-Georges fort, tried to protect the attacked sites and used small-calibre anti-aircraft guns. The shells, at the end of their trajectory, exploded at high altitude and the fragments fell to the ground at random.

Simone Carcouët, who lives at 10 rue Transversale, was injured by a piece of shrapnel that remained lodged between two ribs and that the doctor was unable to extract. Mrs. Prospéro also recounts that "a piece of shrapnel fell down the stairs and bounced into the kitchen right next to her foot.".

Other objects fall from the sky and intrigue the population. These are paper strips of variable length, up to 30 cm, covered with aluminum on one side. These strips are dropped in rain by the planes and act as decoys. Used en masse, they jam German radars and hinder the detection of plane wings.

After the liberation of Paris, air activity moved eastward, not without the Luftwaffe successfully raiding Paris on the night of 26-27 August, causing a lot of damage in the capital (Bichat hospital, Bd Diderot, etc.) and the southern suburbs (which is why the American anti-aircraft guns were set up in Limeil). Finez, who may have seen the flashes, wrote: "…obviously the war is not over…" It would last another nine months!

|

Resistance at Yerres

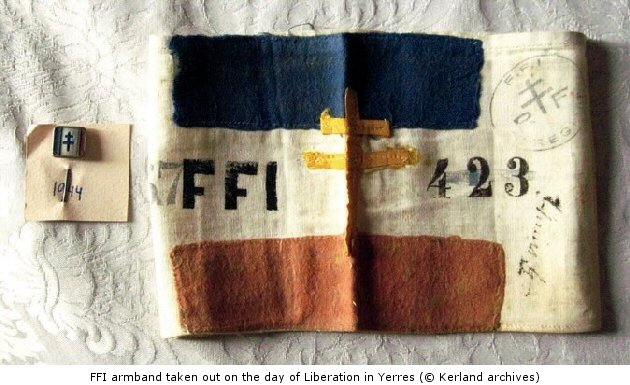

Little-known subject! And that’s normal because it was an activity that obviously had to remain discreet and, after the conflict, there were many other tasks to undertake. Let’s also be clear-headed: declaring oneself to have been a member of the Resistance at the liberation was recognition for past action and a gateway to the future. On the day the town was liberated, Mmes Pernette and Prospéro noticed a proliferation of FFI armbands to the point of being very surprised to see so many Resistance members in Yerres.

There was, however, resistance in Yerres, but, as everywhere in France, it remained low-key until after 1942 and even in our area until 1944, on the eve of the landing. The resistance began in the free zone, very early, and it developed after the complete occupation of the national territory by the German army, first by the creation and establishment of other networks.

At first, the resistance actions, often individual, were limited to the search for information, the publication of a clandestine press, the printing and distribution of leaflets, sometimes, but rarely because the risks were great, the sabotage of telephone cables or railways. People gathered to listen to the BBC, when it was not too jammed, and to General de Gaulle. They drew large Vs (for “Victory”) on buildings, etc.

Resistance is first and foremost a common desire not to suffer! Friendships prior to the war played a major role in bringing together like-minded French people, from which politics is not absent.

It was the Communist Party that launched the first "terrorist" actions (individual attacks) targeted against the occupier through its organization called the Francs-Tireurs et Partisans Français (FTPF) which became the Francs-Tireurs et Partisans (FTP), plain. A Yerrois, Mr. Alfred Alavoine, a driver, was shot at Mont Valérien on April 2, 1942. He was one of the hostages shot in retaliation for the attacks committed against the occupying troops. Another Yerrois, René Morin, a resistance fighter within the National Police, was arrested on March 15, 1944 and shot at Mont Valérien on March 16.

The maquis would appear later in late 1943, early 1944 and, to our knowledge, there would be no armed action in our region against the occupier due to these maquis before June-July 1944, as the liberation of Paris approached. On June 6, the day of the Normandy landings, General de Gaulle proclaimed "the insurrection" on the BBC. The FFI (French Forces of the Interior) movement, which appeared in February 1944, brought together under a single name the military groups of the various resistance movements except the FTP.

It is difficult to know who, exactly, in Yerres was part of a resistance movement. Only a certain number of movements, duly identified, were declared resistant, but at the national level and after the war. Eddy and Lionel de Kerland certainly brought together some friends within a local network, but tell us nothing about belonging to a national network (perhaps the apolitical Civil and Military Organisation (OCM)). Subsequent events show us the existence of another network, rather left-wing, linked to the Communist Party and led by Mr. Michel. In fact, the armed resistance action in Yerres seems to have manifested itself rather via Brunoy or via Villeneuve-Saint-Georges, or even Draveil, towns where the military resistance seems to have been more active.

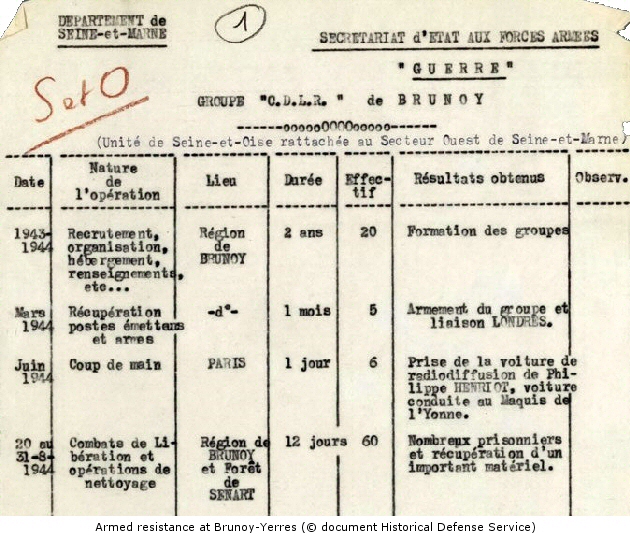

The archives of the Historical Service mention the existence of a Yerres-Villeneuve-Saint-Georges group belonging to the Civil and Military Organisation (OCM), but do not give us the names of the members, nor the nature of their resistance activities. Another group, that of Brunoy belonging to the movement Ceux De La Résistance (CDLR) is credited with military actions in the region of Brunoy and the forest of Sénart between 20 and 31 August 1944.

This does not prevent the people of Yerres from having died fighting or being executed by the occupier during this period of August 1944, proof that some of our fellow citizens participated militarily and actively in the liberation of France. Four of them, whose network of affiliation is not well known (OCM, FTP for some), but, at the time, they were all FFI, paid with their lives in various circumstances for their obedience to the order of insurrection of July-August 1944. Here are the names and their dates of death:

Voici les noms et leurs dates de décès :

Pierre GUILBERT (16/08/44)

ean LEGRAND (21/8/44)) Guy GOTTHELF (25/8/44) Jacques BOUTY (25/8/44)

These names appear on the war memorial in our town

The highly politicized resistance organizations that had united within the National Council of the Resistance (CNR) were not going to disappear after the Liberation. The inhabitants of Yerres were called to the polls, as everywhere in France, to elect their representatives and no one could hope to be elected if they did not claim to be part of a form of resistance that was immediately contested, of course, by the political adversary.

|

The Liberation

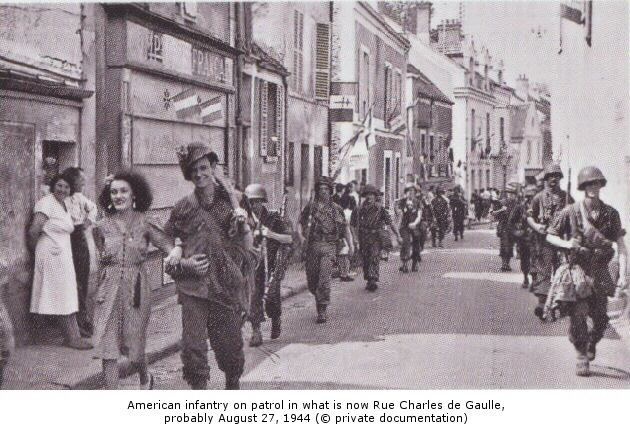

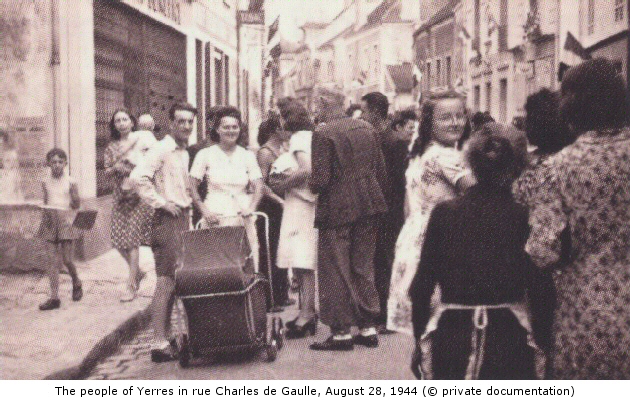

Sunday, August 27, 1944 is a special date for Yerres. It was that gray day when an American jeep arrived on reconnaissance in the streets of the city. The hour of liberation had come.

As a reminder, the Allied armies landed in Normandy on June 6, 1944. After difficult fighting, they managed to break the lines held by the retreating Germans. On August 25, 1944, Paris was liberated by the soldiers of the 2nd Armored Division commanded by General Leclerc and with the support of the 4th American Infantry Division.

The jeep is on reconnaissance and is carrying three soldiers, namely: the driver, the gunner with a machine gun and a radio navigator. The latter transmit at regular intervals all the information necessary for the advance of the allied forces. Speaking English, a Yerrois resistance fighter, Mr. Lionel de Kerland, son of Mr. Eddy de Kerland, also a resistance fighter, is designated by the local resistance group to act as interpreter.

Lionel de Kerland informed the American soldiers that no German infantrymen were on the territory of the commune, but that a section of three Panther tanks were located at the Château de la Grange and in the woods of Gros-Bois, specifically at Notre Dame, to protect the retreat of their army towards Germany.

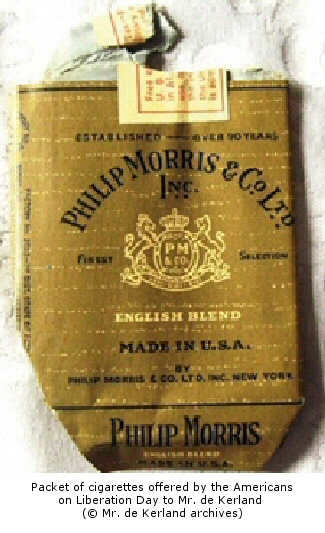

When the news of the liberation of Yerres spreads throughout the town, joy breaks out, the bells of Saint-Honest ring, the windows are covered with French, American or English flags that bloom everywhere. The population gathers in the streets. They happily exchange handshakes, fruit, and packets of Philip Morris cigarettes. The town, out in the streets, cheers its liberators. After the morning mist, a hot summer day begins, the people of Yerres rediscover the joy of freedom regained. The bells of the Saint-Honest church ring out in full force. They chime to announce the 10 o'clock mass.

When the news of the liberation of Yerres spreads throughout the town, joy breaks out, the bells of Saint-Honest ring, the windows are covered with French, American or English flags that bloom everywhere. The population gathers in the streets. They happily exchange handshakes, fruit, and packets of Philip Morris cigarettes. The town, out in the streets, cheers its liberators. After the morning mist, a hot summer day begins, the people of Yerres rediscover the joy of freedom regained. The bells of the Saint-Honest church ring out in full force. They chime to announce the 10 o'clock mass.

The church is packed and it is during mass that the American units arrive, first with a dull roar and then with a deafening crash. They belong to General Patton's 3rd Army. The column of armoured vehicles and other vehicles turns in front of the church towards the Abbey. The people of Yerre gradually discover in front of the Saint-Honest church the columns of American Sherman tanks, Halftracks, cannons, and armoured cars flown over by a piper-cub (an aircraft) at an altitude of less than a hundred metres.

This parade of tanks will last from 10:30 to 8:00 p.m. Almost all the inhabitants are in the street and cheer the liberators. The day becomes very hot; the sun has chased away the mists and the freshness of the morning. It is more than 28 degrees. The people of Yerres, in overflowing joy and gaiety, distribute the harvests from their garden, flowers or bottles of wine. The weather gradually deteriorates and the day will end with a storm.

A supply and engineer unit was set up under the two-hundred-year-old beech trees on Avenue Gourgaud and at the Beauregard estate: dozens of Sherman tanks on their trailers, tanker trucks, earthmoving equipment, etc. These machines bore witness, to the great delight of the people of Yerres, to the overwhelming American power at the end of the conflict.

From a logistical point of view, the municipality and the American forces have reached an agreement on the conditions and amenities of the unit's stationing. The members of the French delegation participating in these negotiations were able to rediscover the taste, after four years of rationing, of real white bread and coffee.

The night of August 27-28 was eventful. For the people of Yerres, it was sleepless. In fact, something that had not been seen since the beginning of the war, there was dancing in the streets. The next morning, a tribute was paid to the Americans, with a parade and a parade in the town hall square (now the Post Office). On the balcony of the Town Hall is a part of the municipal council, including Mr. Perrault, mayor of the city. The Marseillaise and The Star-Spangled Banner, the American anthem, are sung with enthusiasm and joy.

Yerres is free but the war is not over! For example, on August 26, 1944, the Luftwaffe launched 150 bombers to destroy the east of Paris and the Bercy wine hall. The fire was extraordinary and spectacular. It could be seen from the heights of Yerres as the sky was so red. Before returning to Germany, the enemy bombers, flying at an altitude of three hundred meters to escape the Allied night fighters, began their turn above Yerres.

It would be necessary to wait another nine months for the return of prisoners and deportees, and, one could write, the difficulties began. Unanimity against the German would soon give way, in Yerres as elsewhere, to discord between the parties!

|

The Allied "occupation"

Obviously, this is not the same occupation! This one is not only accepted, but even, to a certain extent, desired. After the departure of the German forces, the allied armies will stop at Yerres, either for temporary cantonments (bivouacs of one or two days, or even a few days), or for longer-term stations

Modern armies, especially the Anglo-Saxon ones, need significant logistics to fight and they use what are called combat trains which follow the operational units.

It will be noted that if the sites have changed occupants, they have remained… the same. What changes, on the other hand, is the number of vehicles to accommodate. The poorly motorized German army, often reduced to animal traction during its retreat, had not posed as many parking problems.

Among the transitory and temporary occupations, we can cite the American presence at the Château de la Grange, perhaps not within the grounds of the château itself, which at the time was inhabited by its owner, Baroness Gourgaud, but in the various paths leading towards Limeil and Grosbois, certainly also at the height of the Mare armée. Here, for example, is what Finez wrote a few days after the arrival of the Americans:

"On September 9, very early in the morning, I set off to harvest mushrooms and I saw a camp of American Negroes in front of the Château de la Grange. I stopped and made friends with a few of them. A big devil of a Negro named William Clifford, from Houston, agreed to pose…

He goes on to recount his exchanges with another American who gives him a packet of Camels in exchange for a sketch and he adds "very interesting the visit to the camps" without unfortunately telling us more. There seems to be a relatively permanent parking since he specifies that he returns there on Monday with Francine, his wife, and, he writes, that they go to the Limeil station (it no longer exists, it was the station located on the Paris-Bastille line of the "rose train") where "another anti-aircraft camp is set up".

He trades chocolate and oil for cider and "drop" (which they "are fond of"). He adds mischievously: "…if they stay in Yerres for a long time, they will become corrupt in every way."

In fact, they won't have time since they left on September 13: "goodbye big black kids…", he writes.

This visit to the American camps by the populations is general, especially since the discovery of the American army, its luxury and the abundance in which the GIs bathe, is a real shock for the people of Yerres (and the French in general!) who have not yet emerged from the shortage and who could not even imagine it. The fact that the soldiers are black confirms the presence of logistical units, the American army, at that time, using very few blacks in the operational units. Others will stay longer.

Here is the list of properties occupied by American troops, roughly during the second quarter of 1945 with the names of the owners:

Dr Accad, rue Jacques Bouty; bathhouse; sports ground; Castel 37 rue de l’Abbaye; Duverger, factory rue de l’Abbaye; Hinque, rue Jacques Bouty; Moulin, 1 avenue de l’Abbaye; Bouty, Le Val Ombré; Coignet, Le Manoir. We see that the Germans had often made the same choice.

These occupations were not always without consequences for the people of Yerres, for example the American trucks damaged the walls surrounding the abbey and the rue de l’Église. There was compensation, but it took some time to obtain it. Another example, "Le Manoir" at 5 rue Basse, which, as we have seen, had already been occupied by the German army for a short period in July 1940, belongs to Mrs Louise Coignet, then residing on rue Kepler in Paris. This splendid residence was this time occupied by the American army from April 18 to July 15, 1945. The occupying unit belonged to the Signal Packing Development Station Corps, in other words it was a transmission unit of the US army. This was a kind of amicable requisition for which the French services, the engineering and quartermaster departments, gave the various authorizations.

Mrs. Coignet would wait a long time (July 1948) for compensation accepted by the American army after several years of discussions. It was difficult to determine what had been taken away by the Germans (furniture, in particular) and what had been damaged by the Americans.

The Americans were not the only occupants! Oddly enough, French troops were stationed in Yerres between August 9 and September 14, 1945. These troops belonged to the 1st Motorized Infantry Division (DIM). This division was formed in 1945 by units from the French Forces of the Interior, in other words the resistance fighters, and in September, it joined Lattre's army fighting in the East. It was poorly equipped, partly with recovered German equipment. For reasons we do not know, the detachments were stationed in the localities.